‘Difficult’ names carry value

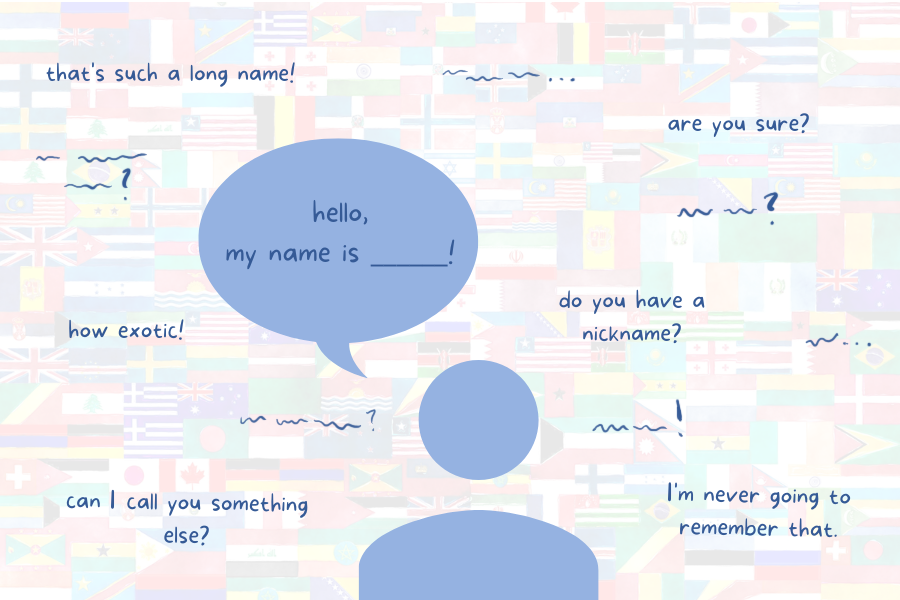

When you don’t have a typical English sounding name, it’s virtually impossible to avoid having someone mispronounce it.

As a 1.5 generation immigrant, I sometimes find myself in an uncomfortable ‘grey area’ between my American and Zimbabwean cultures. 1.5 generation immigrants are those who came to the United States as young children, growing up in American culture and that of their parents.

Growing up in the Midwest with a lack of others similar to me has heightened this insecurity.

My name, however, is a cornerstone of my Zimbabwean identity. Put simply, “Tanatswa” is not a common American name, though it is ordinary in my home country. I’ve never felt the need to change my name, yet others have mistakenly done just this in a variety of amusing ways.

The presence of a substitute teacher inevitably leaves me to wonder how my name will be butchered during attendance, even though my name is pronounced exactly as it’s spelled. The substitute gets through the first few names then pauses, giving up before they even try to verbalize the next name on the list. I say my name out loud, hoping it’s the one they were attempting. This method has has never failed me, and is usually followed by the teacher trying to say it another two to three times before I let them know they’ve said my name “close enough.”

However, this is as far as I’ve gotten in even addressing the mispronunciation of my name.

In order to avoid inconveniencing busy baristas or restaurant employees, I completely change my name to “Lily”. As an elementary schooler, I gave teachers and other adults a shortened version of my name that had previously only been used by my close relatives in order to make interacting with them easier.

Some have even gone as far as assigning a nickname upon meeting me because they won’t remember my real name the next time they see me, or rather, they don’t care enough to get my name correct even after I clarify how to pronounce it.

Peers I’ve met over the years have chosen to go by westernized names rather than their given names, and I could easily do the same. There are an incredible number of people willing to give up a piece of their identity to make others more comfortable, and some do it simply to survive in the western world.

Though unintended, the effects of constant mispronunciation make me feel as though my Zimbabwean heritage takes secondary importance to the American culture I’ve assimilated into. The United States touts a space where people are free to maintain a balance of cultures. Americans can even hyphenate their cultural ethnicities (African-American, Asian-American, etc). Is this bicultural value actually followed through on in day-to-day interactions? When someone mispronounces my name, I suddenly feel a behavioral expectation placed upon me. Having been realized as “foreign”, I begin to overcompensate as the interaction continues, attempting to convince myself and the people I socialize with that I’m just like them. When my name is consistently mispronounced, I feel almost pressured to uphold more American ideals in order to be accepted.

As I’ve grown up, it has become easier to correct people if I know I’ll have to interact with them more than once. However, it’s still tedious going through a series of clarification, followed by excuses as to why my name is “just too difficult,” and a myriad of othering compliments, such as “I’ve never heard that one before,” “how different,” or my personal favorite: “that’s so exotic.’

A person’s name is as crucial to their identity as their race and gender. Names carry personal, cultural, religious and historical significance, and can help us remember where we came from. This doesn’t just apply to “foreign” names that aren’t heard often in the United States; English names also carry significance that span generations, even if they have been adapted to today’s society.

When a name is deemed “too difficult” to pronounce even after it has been clarified over several instances, what this really means is that a person is too indifferent to adapt their current schema of what a name should look or sound like. Suggesting that a name is too challenging because it is foreign gives people a “pass” to look for an alternative or simply disregard the correct pronunciation of that name.

On everyone’s part, accepting such indifference deprives communities of excellent learning opportunities where they could gain knowledge of a new culture other than their own.

Showing respect towards someone’s name and taking the extra time to show them that you’re actively learning, even if it takes you a few days, goes a long way and communicates that you value them. Names are beautiful, they’re special and a large part of one’s identity. By failing to make an effort to get someone’s name right, you effectively other them from your circle.

Though it may not seem like a large issue on surface level, pronouncing someone’s name correctly creates visibility for non dominant cultures- which Westside has plenty of- and is an incredibly powerful way to begin creating an inclusive environment where everyone can belong and contribute.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Omaha Westside High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Hi! My name is Tanatswa Chivero, and I am a Co-Editor in Chief for Wired. I am currently a senior, and this is my fourth year in journalism. If you have...