Reflecting on the Effects of the 1990 Westside v. Mergens Supreme Court Case

Lance news article from Sept. 14, 1990, examining the intricacies of the Westside v. Mergens Case.

It was 1989, and the Mergens v. District 66 case was coming to a crescendo. According to an article published in The Lance on Jan. 29, 1990, the district had spent over $100,000 on legal fees and the case was to be decided by the Supreme Court on June 4 of the following year. Bridget Mergens Mayhews, who was a senior when the case first started in 1985, wanted to form a Bible club at school with the same treatment and access as other clubs, like the chess club. Westside denied Mergens her request because she would not be allowed to have a sponsor (a faculty member) and it could violate the Establishment Clause, which prohibits the establishment of a religion by the government.

At the start of the case, U.S. District Judge C. Arlen Beam ruled in favor of Westside’s board of education, but Mergens appealed, and by February of 1989, the decision was in favor of Mergens. By April of 1989, the board of education asked the Supreme Court to look at the case, and in December they conducted the oral argument.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled that since Westside allowed other non-curricular student clubs it was prohibited from denying clubs based on the content of their speech under the Equal Access Act.

“The Federal Equal Access Act says that if a public high school or school that receives federal funds allows any student group that is not related to the school curriculum, so if they allow any student group that’s not, like, math club, science club, then they can’t deny other student groups the right to be able to meet and have the same access as other clubs,” said Scout Richters, who is part of the Legal & Policy Counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Nebraska.

The Supreme Court justices in the case used the Lemon Test to determine if the Equal Access Act was constitutional, which means they checked to see if the act was secular or religious in nature. They determined that it passed the three step test, meaning the act was not religious and could apply to the Mergens case.

According to a follow-up email with Richters, student-organized clubs, including religious clubs, are permissible in public schools and schools that receive federal funding as long as they follow three guidelines.

“One: the activity must take place during non-school hours,” Richters said. “Two: school officials can’t be involved in organizing or running the club and three: the school must make its facilities available to all student groups on an equal basis.”

Under the Equal Access Act, Westside is a limited open forum, so it cannot deny students wanting to meet and discuss religion, politics or philosophy.

According to Vice Principal Trudi Nolin, the case had an impact on Westside’s policy on club formation.

“I came in ‘94 so I knew it was a case,” Nolin said. “It was close to when I came. I wasn’t doing clubs at the time, I was teaching, so I wasn’t in on it as much. But when I did become the assistant principal the [the court case] was a piece we talked about with board policy about sponsored and non-sponsored clubs.”

Creighton professor and lawyer Richard Mangrum consulted for Mergens on the case and said it impacted more than just school clubs.

“It was kind of the first of a number of cases that came out of kind of an equal protection concept,” Mangrum said. “The Westside case is more important than just the Equal Access statute. It helped generate a number of cases that followed it that were not on Equal Access. They were based on free speech mostly.”

One resounding impact the Equal Access Act has is the formation of Gay-Straight Alliance club (GSA) in schools. Richters also said that the ACLU receives input from students who say they haven’t been allowed to form GSA, have meetings at the same time as other clubs or post the club’s posters on the school’s bulletin board.

“This Equal Access Act, it also protects students to be able to form Gay-Straight Alliances or similar clubs,” Richters said. “If you’re going to be in the business of allowing other clubs that aren’t purely curricular, then administration can’t police what clubs they do and don’t allow based on the employee.”

According to Nolin, there are more than 65 clubs at Westside. One of the most common reasons clubs get denied is because administration is worried members might be taken away from other clubs.

“We have a process, and that is if a student is interested in starting a club, they will come talk with me on what kind of club do they want to do, what’s the outcome of the club, what kind of activities will the club do, what kind of fundraising [they’ll have],” Nolin said. “With 65 [clubs], the reason I like them to come in and we discuss is [I ask], ‘Are there any clubs that resemble it [or] that are very close?’ … It might be something that we could combine the one that they want to create and the one that we have already.”

When it came to making the policy, Nolin said she worked with the human resources department on the process to make sure people were able to join the clubs they wanted to.

“We looked at area schools and their process for clubs being formed by students,” Nolin said. “The interesting piece is when we did look at places in the metro, lots of places don’t have near as many [clubs] as we do. I feel like we are very lucky to have that many, and I feel like it’s lucky for our students to have that many for them to be involved [in]. Our ultimate goal is for them to have a place to be involved.”

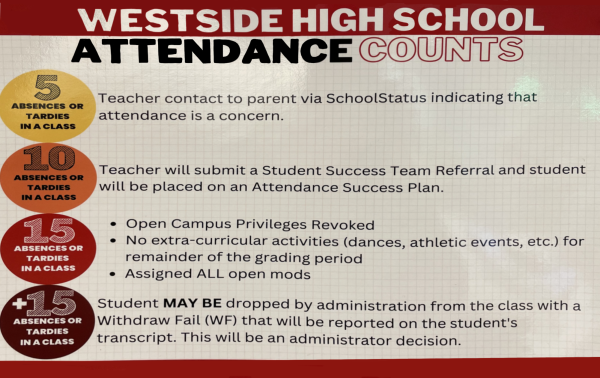

According to Westside Board Policy 5610, Westside can have two categories clubs can fall under: sponsored and non-sponsored. To form any club, students must fill out paperwork demonstrating that it complies with school guidelines. These include having sufficient student interest (about 15 students), complying with board policy, having a staff member willing to supervise meetings, having a structure and objective, being inclusive and being significantly different from other established clubs. This paperwork is then reviewed by administration, who determine whether the club is allowed to be sponsored or not.

“The school shall not sponsor a club where the mission or activities of the club are: 1) religious or political or the club is affiliated with any religious organization or political party, organization or campaign; 2) contrary to the educational mission of the school; 3) in conflict with any oard of Education Policy, including Board Policies 2211 (Prohibition of Sex Discrimination), 2215 (Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability) and 2218 (Nondiscrimination); or 4) are adversarial, subversive or secret in nature,” Board Policy 5610 reads.

Non-sponsored clubs are not allowed to have a staff sponsor, hence the name, and are not under school direction or control. Because of the Mergens case, however, they are given the same resources as sponsored clubs in terms of access to space and the ability to make announcements over the intercom, put up posters and put information in the announcements, as long as they are previewed by administration. The school must also assign a monitor for the club for safety purposes.

“[Staff members at non-sponsored clubs are] merely there to make sure everything’s going okay with everybody in there, not necessarily giving their viewpoints,” Nolin said. “The only [thing] that really becomes a concern is when [the teachers] are on their contract time. So, like 7:45 to 4:00, those are their contract times. That’s the time they are a supervisor not giving viewpoints or anything. It can be a little different when they are outside their contract time though.”

This distinction came into play in December when junior Jack Moseman founded the Young Republicans club. The club is a sponsored club with a paid supervisor, social studies instructor Brian Nemecek. Because he is getting paid and is within his contract time, Moseman said Nemecek does not give his personal political viewpoints. According to Moseman, he is the one who usually runs the meetings, and Nemecek primarily makes sure the club has a space to meet.

“[Nemecek] doesn’t have a really large role,” Moseman said. “I kind of run the meetings or I’ll set up an agenda for the meetings, and then I’ll turn it over to our speaker.”

When the Young Republicans group was petitioning to be a club, Moseman said he had to clarify the purpose of the club to administration.

“I wasn’t worried about them just saying no, because our club it’s not about [saying], ‘I’m right, you’re wrong,’” Moseman said. “It’s not about excluding people who, if you don’t think this way about this policy, you’re not invited. That’s not our club. That’s not what we do. We are providing networking, and we’re providing opportunities to our members to get involved. That’s what we’re really doing.”

As the club technically is focused on government as a whole and not specifically the Republican party, it is allowed to be sponsored. The Fellowship of Christian Athletes (FCA), on the other hand, is not. This club brings together Bible study with sports and resembles the club Mergens tried to start years ago. Despite being unsponsored, it continues to meet weekly at the high school and has 20 regular members.

FCA member and junior Christina Manna said the club allows students to find a like-minded community at school.

“It gives you more people to be in contact with to not only discuss things that you wouldn’t normally discuss in … an everyday context, and also to not be alone, in a sense,” Manna said.

Librarian Theresa Gosnell is the club supervisor and also one of the main organizers for the club. She said she helps schedule the meetings and emails the members about their weekly Thursday meeting conducted at 7:15 a.m. Gosnell said she believes the group offers students the opportunity to express their beliefs. Every other week, the club alternates between playing games or Bible study.

“Everybody has different beliefs and so this is one … [where] people can meet and talk about their faith,” Gosnell said. “It’s just another thing that people believe in. It’s called Fellowship of Christian Athletes, but it really could be anybody that believes and wants to come and learn more.”

Before starting the club, Gosnell and the other sponsors made sure they were allowed to have Fellowship of Christian Athletes at Westside. They contacted an FCA representative who said they were allowed to have the club with some conditions.

“We rented out the church across the street because we didn’t think we could have it,” Gosnell said. “We didn’t think we could have it, but we are able to have it. We just can’t have it sponsored by us. Really, it’s supposed to be kid-led.”

Manna echoed the Supreme Court’s ruling when describing the importance of FCA being allowed to meet as an unsponsored club on campus.

“The way I see it would be we have all kinds of clubs here, right, and there are all kinds of different belief systems,” Manna said. “Every club has its own, not religion, but belief. So, if one wasn’t allowed because of what it believed, [it wouldn’t be fair].”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Omaha Westside High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Hi, my name is Malia Battafarano! I am an Editor-in-Chief for Lance this year. I am currently a senior and this is my fourth year on Lance. If you have...

Hi my name is Maryam Akramova! I am an Editor-In-Chief for Lance this year. I am currently a senior and this is my fourth year on Lance. If you have any...