Viral Ebola myths hold us back

One year ago, I stood in room 202 with sweaty palms, facing rows and rows of desks occupied by my entire Intro to Health Science class. I fumbled as I plugged the USB drive into the side of my MacBook and glanced at my partner. The first slide of our PowerPoint popped up onscreen, displaying a long, pretzel-shaped strand of RNA.

“Hi, guys. Uh, so for our disease presentation, we did the Ebola virus…”

The topic had interested me. After one week of flu-like symptoms, victims in late stages begin to bleed out of every bodily orifice — and yes, that includes the eyes and ears. It’s a truly horrifying disease, and at the time of my presentation, most Americans weren’t even thinking about it.

Recently, I was sitting in the cafeteria and sipping spoonfuls of the latest soup when I overheard a conversation at my table. Something about how the virus will escape, and that the government is going to impose martial law, quarantine Omaha and exterminate the population.

This sentiment isn’t new. In fact, it’s encouraged. Sometime during Intro to Health Science, our class watched the 1996 film “Outbreak.” It featured a hemorrhagic fever that originated in Africa — pretty clearly inspired by Ebola. Its main plot was what my table-mate had predicted: the U.S. government was going to level an entire suburb that had become infected. There were military planes, plenty of dramatic music and a high death toll. Now that two Ebola patients have received treatment at Omaha’s University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), people wonder if the future of our city involves a similar doomsday scenario.

In all likelihood: no.

Read the rest of Lance Issue Three here:

I figured this out by speaking with Dr. Jessica Snowden, an assistant professor on the topic of pediatric infectious disease at UNMC. She put it this way: Nebraskans should probably be more worried about the common flu.

This is partially because the Ebola virus is transmitted through direct contact with bodily fluids, which makes for a slow spread and simpler containment. Unlike other viruses that have caused mass pandemonium such as H1N1, there will be no sneezing, sniffling or coughing to spray a massive cloud of infectious Ebola droplets into the air we breathe.

One objection could be made using the nurses who got infected in Dallas, Texas. However, unlike the Dallas hospital, facilities at UNMC are specifically designed to handle infectious disease, as conveyed to me by Snowden. Their website elaborates: UNMC Ebola patients are treated in a sealed biocontainment unit with expertly trained staff. It is in a separate building and has its own air handling system. The facility was built to house the deadliest diseases known to man, such as smallpox. The chance of a breach with that level of security is slim.

Yet another fear is that the Ebola virus will mutate to become airborne (which would mean it would be transmitted quickly by sneezing and coughing, through droplets in the air). The truth is, Ebola has been around in primates for many, many years, and it’s extremely unlikely that Ebola would suddenly mutate into an entirely different type of disease. A statement from the World Health Organization featured on CNN says that such a scenario is “speculation, unsubstantiated by any evidence.” Even scientists that say Ebola could theoretically become airborne do not have a single example of a similar change in a human disease’s mode of transmission. “Could” is the key word here. For example, a meteor could crash into your house, right now — but there’s no sense worrying about it unless it actually happens. It’s the same deal with Ebola.

I’ve also heard many Ebola conspiracy theories, both from well-known figureheads and perfect strangers I’ve talked to in line at Chipotle. No, the government did not introduce Ebola into the U.S. on purpose. Instead, probability is the one at fault: the ease of modern travel means viruses can travel around the world quickly. Besides, if there were a conspiracy to kill U.S. citizens with Ebola, the government wouldn’t be working so hard to contain it (recently, an airplane was evacuated because someone joked about having the disease).

Statistics are really the final arbiter here. So far, one person has died from Ebola on American soil. According to the CDC, in recent history, the amount of people who have died from flu-related complications each year has ranged from 3,000 to 49,000. Until Ebola’s death toll in the United States gets even remotely close to that low of 3,000, there’s no reason to start buying HAZMAT suits or blaming the government because it’s statistically less dangerous to us than the common flu — a disease that many people actually refuse to get vaccinated for.

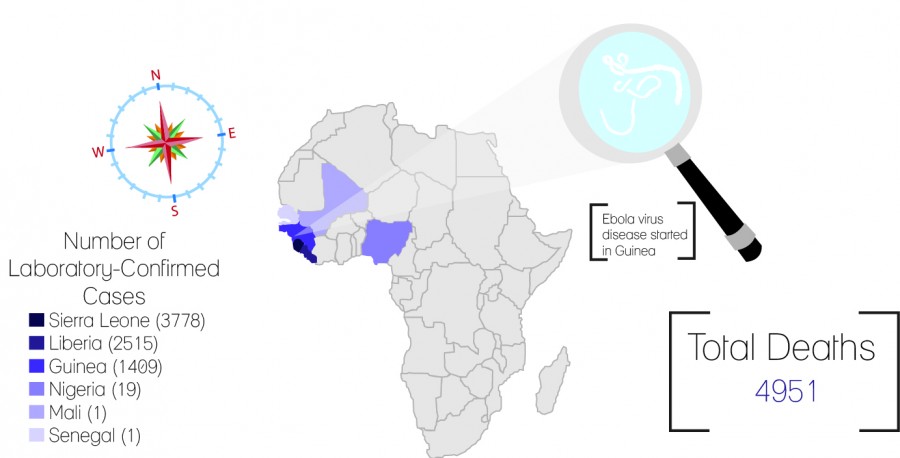

I’m not saying we shouldn’t be thinking about Ebola because we absolutely should. I am saying that for now, it’s time to stop prepping ourselves for the doomsday scenarios shown in films such as “Outbreak.” It’s fine to be afraid and ask questions. However, we also have to be rational. There’s little we as individuals can do save for complying with CDC recommendations, practicing good sanitation and getting vaccinated (when and if a vaccine becomes available). With all the evidence, it’s clear that America can handle a local pandemic. Let’s focus our efforts on the countries and people who are actually being affected.

If we do that, I believe humanity can work together to stop this virus on the front lines. The media likes to focus on negatives so often that we forget we can accomplish amazing things. For instance: so far, both of the patients who entered UNMC’s doors have been successfully treated. With international cooperation, we may even be able to eliminate the disease worldwide — but only if the panic stops. We should not be trying to insulate ourselves. Instead, we should be trying to pave the way forward.

This column first appeared in Issue Three of the Lance, which published Nov. 7, 2014. Pick up a copy now!

Your donation will support the student journalists of Omaha Westside High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.