Your donation will support the student journalists of Omaha Westside High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

A SHORTFALL: Budget forces district to make tough decisions

Other schools face similar situation

April 17, 2015

For English instructor Eric Sayre, 30 extra students in one semester means 10 extra hours of grading per essay. 30 extra students means his desk arrangement in room 130, a circle of 22 desks meant to enhance his discussion-focused classes, might not work as his per-class average hits 22 students.

“It won’t look like what it’s been looking like in my class, which I think is an inviting environment that welcomes thoughtful discussion and where kids, I think, flourish,” Sayre said. “It will be very different.”

Science instructor Micala Donnelly’s classroom will look even more different. It won’t even be in Westside; she’s accepted a job at Abraham Lincoln High School in Council Bluffs.

Spanish instructor Trevor Crowell will see the same difference. He’s looking for a teaching position in California, where his girlfriend will be studying for her PhD at Stanford.

Sayre, the most-tenured teacher in the English department with 17 years of teaching in the district, has seen this happen before. With stagnant or shrinking revenue, rising costs, shifting demographics or a combination of the three, District 66, like other districts in the Omaha Metro, has found itself forced to make changes to its spending.

In recent years, this has meant, at worst, decreasing teacher numbers via attrition. This time around, it means English instructors will be taking on increased numbers of students as two teachers, Chanel Colt and Elizabeth Leach, take one-year leaves of absence without replacement; the science department will see a teacher position switched from the high school to the middle school; Crowell, who was hired to replace another Spanish teacher on a leave of absence, will not be coming back to the district and District 66 will have to absorb a $2.5 to $3 million shortfall.

It’s a multi-faceted problem for the district, its teachers, its students and its homeowners. Revenue for the district is tied to a number of uncertain and often unpredictable sources like the Nebraska state legislature, district property values and federal aid. Expenses, meanwhile, rise constantly; teacher salaries have to increase, costs for employee healthcare packages are rising at a faster pace — 6 percent last school year — than the overall cost of living and buildings need to be updated and repaired.

As Sayre puts it, he is not necessarily mad at the district. Neither is Crowell. Neither is Donnelly.

For Sayre, Crowell, Donnelly, Colt and many other teachers, the worries and frustration mostly revolve around one thing: students. The uncertainty with the district’s budget, teaching positions and more are requiring choices with uncertain consequences.

————————————————-

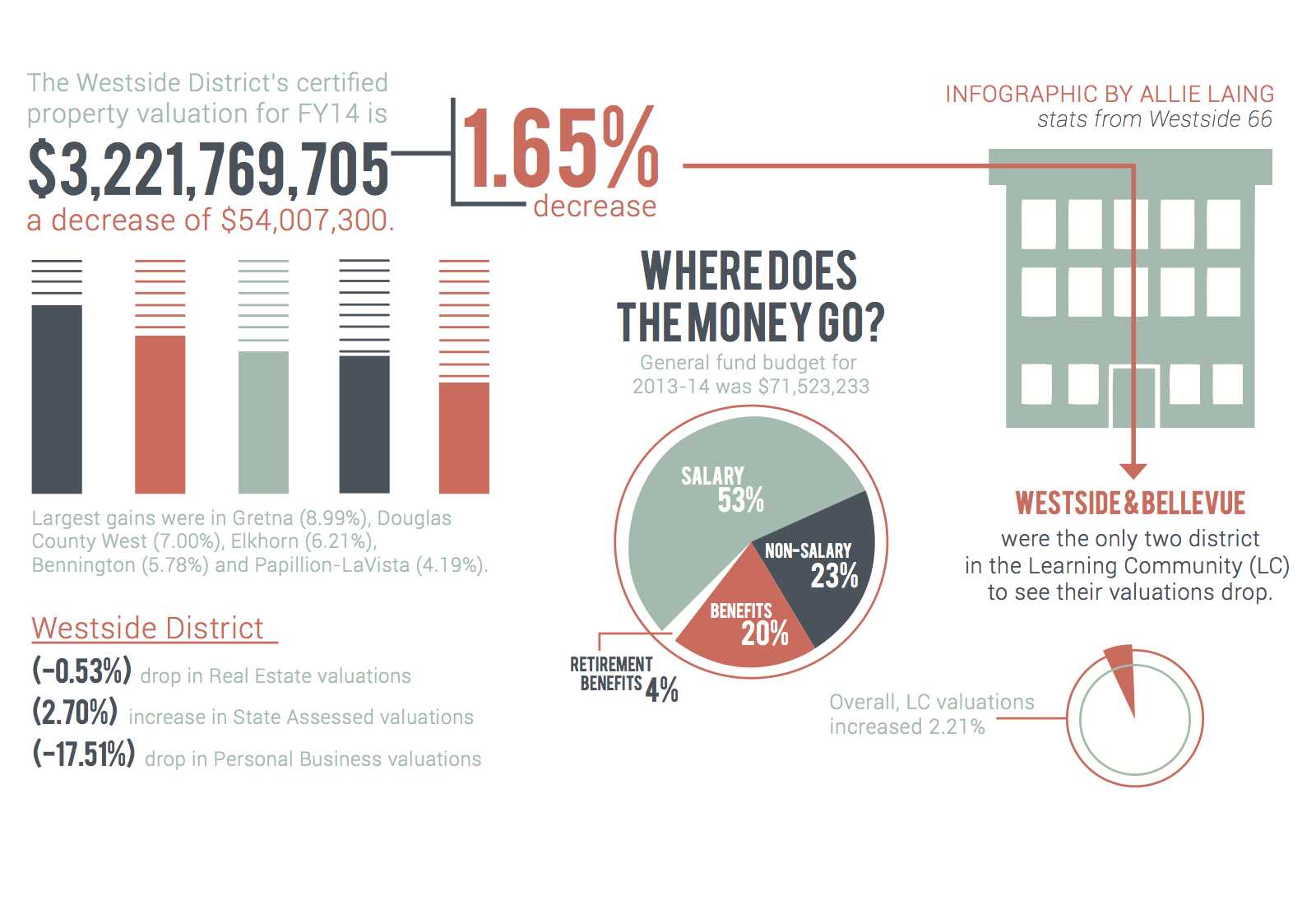

Last school year, 77 percent of the district’s budget went to salaries and benefits, and trimming from the largest part of the budget is one of the main ways the district is looking to limit its shortfall.

“Staffing — that’s where most of your money goes,” Westside High School Principal Maryanne Ricketts said. “Not just here, but at all of our schools, [if] there’s a way we can absorb teachers that are leaving for retirement or changing jobs, that’s what we’re looking at, at this point.”

This is where Crowell, Donnelly, Colt, Leach, Sayre and many other teachers are affected.

Crowell and Donnelly will be leaving Westside. Colt and Leach will be taking leaves of absence and won’t have their spots filled for the year (and might not have jobs at the high school when they return). Sayre and the other English teachers will be taking on significantly increased student loads. Science teachers, too, will have increased student numbers.

Media Department instructors will be taking on senior project teaching responsibilities. In addition, Intro to Speech will become a first semester-only class, creative writing will be offered second semester only and regular debate will be combined with advanced debate.

Donnelly, the least-tenured teacher in the science department, will see her time at Westside end after two years. According to Donnelly, because she has been at Westside the fewest years of all the science teachers, when a science department position was cut she was the one to go. She was offered a job at the middle school, but ultimately elected to leave the district to continue teaching high school.

Donnelly said the way she found out about her position being cut was less than ideal. In March, Donnelly was called to a meeting with Ricketts and science department head Brenda Zabel. She was told that her position was being cut, something she didn’t know was a possibility, and that she had 24 hours to decide whether to stay in the district or leave.

“This was a huge shock,” Donnelly said. “I had no idea that my job was being taken away from me, and so I needed to think about this, and I needed to talk with my husband.”

The district ultimately “backed off,” as Donnelly said, and gave her more time to decide. Within five days, she found her future job at Abraham Lincoln, where she had student taught. She said the district was sincere and wanted to keep her in the district. Regardless, Donnelly would have liked “a bigger heads up.”

“I think other teachers will understand [that] most often for teachers to get hired — to apply to another school, to go through that process, to get a call back to interview — it could potentially take a month,” Donnelly said. “To think that I had this choice to make in 24 hours, or even a week, that’s ridiculous… Obviously they knew budget cuts were going to happen. They could have maybe made this clear to all new teachers that this could potentially happen to them so that I could have been looking for other options.”

Ricketts said the district does not comment on specific personnel cases, but said the administration has never really had to make cuts like it has this year. She added that these decisions are emotional for the administration, too.

Crowell, meanwhile, was hired for this school year to replace Spanish instructor Amanda Freitag while she took a one-year leave of absence, something the district allows teachers to do with the guarantee of a job within the district upon return.

When hired, Crowell was guaranteed a teaching spot within the district beyond his first year. However, that spot turned out to be either a middle school or non-Spanish high school position, things Crowell wasn’t interested in taking.

“It’s disappointing for sure, but I’m not bitter towards Westside or the administration,” Crowell said. “It’s just an unfortunate situation. I don’t regret coming to Westside.”

Crowell praised the administration’s handling of his case, saying they offered him different options and were “very empathetic.”

Donnelly and Crowell were offered jobs at the middle school because, according to District 66 Superintendent Blane McCann, the middle school is understaffed. McCann said the shifting of positions was not, in fact, caused solely by budget changes.

“Usually in a middle school, a group of four teachers will serve approximately 125 to 135 students,” McCann said. “Ours are serving 166. Consequently, we perceive ourselves as being a little bit understaffed… It just made sense to look at shifting some folks from the high school to the middle school to really achieve [the] middle school philosophy [of having small learning communities].”

Of course, Donnelly and Crowell understand why the district wants to move positions to the middle school. However, they are both worried about possible effects of non-continuity in teachers for students and of increasing class sizes. Donnelly said she was most emotional when telling her homeroom students, with whom she has developed strong relationships.

While Donnelly and Crowell are worried about effects on students caused by departure, Sayre and other teachers are worried about the effects on those that are staying.

“I have four kids, and [I’ve been] married going on 17 years, and my family deserves to have a dad who’s around to do some of those nice things,” Sayre said. “When I put my kids to bed, usually at 8 o’clock, that’s when I go grade papers.”

With those 30 more papers to grade, Sayre sees either time with his family or class rigor diminishing. For the first time in his teaching career, he is considering adding page limits to essays. He and other English teachers have also discussed turning summer writing assignments into summer reading assignments.

“The thought of 30 more papers and how I can fit those in, it seems like an impossibility,” Sayre said. “…I don’t feel like those are good things, and I don’t feel good about that as a teacher, but I also feel like we’ve been pushed up against a wall, and there’s no choice but to come up with some way to maintain our sanity and still give the kids the best experience they can…Things will change, and they won’t be for the better.”

Colt, who will be using her leave of absence to spend time with her son while attempting to grow her online baby clothes sales business, did not know she and Leach would not be replaced until, according to her, the week she had to confirm that she would be taking a leave of absence.

“Obviously, that’s a lot of pressure on me,” Colt said. “…It’s just an unfortunate situation that, really, I didn’t know about until I decided to take the year.”

She, like Sayre, is worried about the effects of having no replacement during her leave.

“I’m more concerned with the class numbers [than if I’ll be teaching high school or middle school when I return],” Colt said. “The fact that they’re not replacing me is more stress on the teachers, less time to plan, more students at their desks during open mods.”

McCann and Ricketts both said the district has done its best to keep cuts from affecting classrooms. They are confident, as well, that teachers will be able to adapt to all of the changes.

“It’s going to be a little bit different for the teachers, but I think our teachers are very capable here,” Ricketts said. “They’re good with instruction, and we’re not planning on seeing any significant changes in the classroom.”

————————————————-

As District 66 Chief Financial Officer Bob Zagozda explains, if expenses are growing more quickly than revenue, the two will meet. Eventually, that means costs will exceed the incoming funds. Currently, that is where the district stands and how its expenses are $2.5 to $3 million greater than its revenue for this year.

“Revenue is much harder to affect [than expenses] when you’re a public school district,” Zagozda said.

In short, the district pulls its revenue from two main sources: state aid and property taxes. Both are tied to the Learning Community common levy formula, which was first put into effect for the 2010-2011 school year.

The idea with the Learning Community was to freeze district boundaries, preventing a merger of all of the Omaha districts into one full-city district, in exchange for pooling all of the districts’ tax levies into a common levy. Funds from this common levy are distributed from the pool based off of district size. As a district’s student population increases relative to other districts, it gets a larger slice of the pie. The goal was to provide districts with lower property values and thus a poorer populace more levied funds while promoting socioeconomic diversity in all of the districts.

Of course, the plan is more intricate than that. But the levy goes like this: each district is allowed to take $1.05 per $100 of valuation from property owners within its district. $.95 of that goes into the Learning Community common levy pool. The other $.10 goes directly to the school district whose property it was levied on. On top of that, schools can add a $.10 levy override — Westside is one of the only schools that has passed an override — and take that extra $.10 directly. Schools can also pass bond issues that increase the levy amounts, although bonds are used to address building construction, not things like teacher salary and other general expenses.

Under the Learning Community, District 66, which has had roughly the same number of students for 15 years — just over 6,000 — is receiving a smaller and smaller piece of the common levy funds as other districts increase in size.

“The formula favors those districts that keep growing a little bit,” Zagozda said. “We’re just not there anymore.”

Meanwhile, property values in Omaha and District 66 have been relatively stagnant since the Great Recession of 2007-2009. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a federal stimulus package aimed at combatting the effects of the recession, helped the district combat static property value-based revenue, but that package ended in 2012. After that, the district found itself in a similar situation as now and had to cut expenses.

For this school year, a big hit to the district’s revenue came from a 17.51 percent decrease in personal business valuations, which factor into the valuation of the district. The decrease was due, in large part, to the loss of Blue Cross Blue Shield property, which was sold to non-profit Alegent, and to a decrease in the Crossroads Mall valuation. This led to an overall drop in district property value of 1.65 percent according to a Sept. 22 report to school board members by Zagozda, making Westside one of only two districts — Bellevue was the other — in the Learning Community to see a decrease in property valuation.

“The only thing you can control, really, is what your spending is,” Zagozda said.

————————————————-

It’s hard to gauge what the immediate impact trimming expenses will have on students in District 66. But one thing is clear: this isn’t a Westside-only problem, and Westside appears to be weathering the storm better than many.

According to the Omaha World-Herald, at its March 16 school board meeting, Millard Public Schools board members discussed proposals to cut entire programs, including its Japanese program and culinary-skills academy, to trim its budget.

Bellevue Public Schools, the hardest hit of the districts as it is preparing to lose significant federal aid because of a decreasing percentage of children of military families, is looking to cut expenses by $4.5 million, according to the Omaha World-Herald. As many as 38 positions in the district could be eliminated.

“If you read the news, every school district is looking at, ‘What can we do to work our budgets, stay in our budgets, [and] provide good education?’” Ricketts said. “This is not just Westside Community Schools that’s going through this right now. We’ve just got to make the [state senators] in Lincoln say, ‘Schools need bigger budgets to work on.’”

Whether Westside will get that bigger budget or not is hard to tell. State aid varies based off of the state legislature, which can be unpredictable. McCann said the district might be getting a smaller chunk of state aid for certain parts of the budget next year, but other parts might see increased funding. In reality, state aid is unsure.

Property values are updated at the beginning of every school year, but McCann said estimates look like Westside could see a 4.5 percent increase in property valuation. That, of course, would provide a significant revenue boost.

Zagozda said the district is also seeking out more grants to supplement revenue. The district won the Youth Career Connect Grant, which Zagozda said boosts revenue by just under $1 million per year.

On the spending side, the proposed $79.9 million bond issue, which is going to voters at the end of April, would help the school reduce energy, water and building maintenance costs over time if passed. Energy savings alone could be as much as $100,000 per year.

In addition, the district is continually rebidding its contracts for transportation and other services in order to save money.

The bottom line is this: there is still much hope in Westside. A touch of good fortune and some education-funding legislation could turn things around as far as budgets. Administrators and teachers alike think District 66 still has a significant draw for young teachers looking for a job, people looking to move into a neighborhood with steady property values and families looking for the best education.

“I still think Westside has a draw,” Sayre said. “I’m worried that three, four years, five years from now, maybe we’ll lose that, maybe it’ll slip. I still think Westside’s a desirable place to teach.”

A shortened version of this article was originally published in issue seven of the Lance. Make sure to pick up a copy of the issue today.